This web page provides an overview of my project to provide modern foundations for the criminal justice systems of the West. My goal is to provide a new basis for decisions on policy questions such as whether the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard is the right one, whether majority verdicts should be allowed or whether to allow different kinds of evidence to be presented to the jury. These sorts of policies have a big impact on who does – and doesn’t – get convicted and so are at the heart of arguments over, for example, the way the law deals with rape. The idea is to use mathematics to think clearly about the trade-offs involved in such policies and measurement to ensure that our decisions reflect a democratic mandate.

The one legal principle my father taught me was “Blackstone’s Ratio”, the dictum that, “…it is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer”. That this should come from a civil servant with no legal training is not surprising as the law in Anglo-Saxon jurisdictions has for centuries used this statement to buttress its authority. But what does it really mean, why did it become so important and what are the implications of its decline from incontestable to contestable in recent decades?

It seems obvious that there is some kind of trade-off between the innocent suffering and the guilty escaping, what we refer to today as false (or wrongful) convictions and false acquittals. For example, if we allow into court more evidence of past bad behaviour by the defendant it is likely that we will reduce the number of false acquittals but may also increase the number of false convictions. So the dictum seems to express a valid value judgement that ought to be consequential and in this way I think Blackstone promised a basis for policies that seemed quantitative, objective and democratic – in a word, modern. No wonder it was popular.

But Blackstone, writing in the 1760s, failed explain how to make the value judgement consequential. It isn’t clear how one gets from the ratio of 10:1 to any particular policy, as opposed to one slightly stronger or weaker, or indeed much stronger or weaker. Equally, it isn’t clear what policy options and practical consequences we should be comparing if you advocate 10:1 and I advocate 100:1. There is a methodological gap. Thus Blackstone’s Ratio left the law in an awkward state, half in and half out of modernity. Subsequent generations have been unable to fix the problem and gradually the lack of a cogent argument has I think caught up with the dictum, which has become less central.

Today, the half in, half out quality is still visible as legal scholars try to move on. Some have adopted a fully quantified approach to policymaking, based mainly on an equation put forward by Kaplan in 1968, and some have explicitly rejected quantification altogether. The quantitative approach is more common in the US and the non-quantitative more common in the UK, but there’s a mix everywhere. And so, surprising as this may be to those who are not involved with the law, there is today no settled basis for most of the policies governing the way the criminal justice system operates. Despite having enormous criminal justice systems we in fact have no clear idea of what criminal justice itself is.

I regard both the current attempts to resolve the problem bequeathed to us by Blackstone as flawed, the Kaplan-based work for methodological reasons, the unquantitative because the democratic promise we found in Blackstone seems too precious to abandon. Instead, I frame the law’s underlying problem as one of measurement, specifically the question of how to measure the degree of success of the system in distinguishing between the guilty and the innocent. It’s foundational work and this brings in questions of jurisprudence, history, sociology and philosophy.

I lean heavily on:

- the distinction between the epistemology of the courtroom and meta-epistemology of policymaking provided by Laudan

- the idea of a sovereign in Bentham and Austin, and the limitations of that concept as established by Hart

- the distinction between subjective and objective conceptions of probability, most clearly set out in the legal context by Dawid

- Franklin’s history of probability, broadly conceived

- Hand’s idea of pragmatic measurement

- the statistics of evaluation used in information retrieval, particularly Van Rijsbergen’s F-measure

- the role of quantification in providing objectivity and trust, as described by Porter

- Shapiro’s historical account of the crisis of proof in the early modern period when English law lost access to divine guidance through the medium of Christian conscience

- Volokh’s survey of “n law”, an enthusiasm for variants of Blackstone’s ratio in the decisions of courts in the US and elsewhere

- Rawls’s framing of justice as a distributive question of how the great institutions of the state allocate rights, duties and advantages.

The whole thing can be seen as a kind of riposte to Tribe’s warning that the introduction of mathematics into the law would prove “more dangerous than fruitful”, as a fulfilment of Laudan’s ambition to develop a rigorous meta-epistemology for the law, and as a way of making good on the promise that we found in Blackstone.

Publications

So far I have written five articles, of which the first two have been published, the third has been accepted, the fourth is being considered by journals, and the fifth is still in draft.

1. Killing Kaplanism: Flawed methodologies, the standard of proof and modernity will appear in the International Journal of Evidence and Proof in 2019 but has already been published through Sage’s “Online First” programme.

This aims to clear the decks for new quantitative work by definitively refuting on methodological grounds existing quantitative approaches to the standard of proof based on Kaplan’s influential 1968 article. I also claim to refute Kaplow’s law-and-economics approach.

It also sets out my general programmatic goals more fully than here. In doing that, I closely examine Blackstone’s ratio and develop the half-in, half-out idea more fully. Blackstone used the dictum as part of a three-step argument to justify the adoption of two specific policies, one of which was to never convict of murder or manslaughter unless the body can be produced. What could explain its monumental subsequent influence?

The explanation seems to me to likely lie in a combination of four factors: the new need for a justification for policies identified by Shapiro; the usefulness therefore of the very general applicability of steps one and two in Blackstone’s argument; the dictum’s quantitative aspect, which chimed with the beginnings of the general adoption of the quantitative in society at large, a movement which at about the same time gave us Beccaria’s la massima felicità divisa nel maggior numero; and the ability of the dictum to be read as shoving policy-makers towards policies that reduce both the number of wrongful convictions and the ability of the state to seize and convict, which chimed with the new and popular demands of the emerging democracies and was in contrast with other contemporary frameworks, such as that noted by Franklin which invested judges under Robespierre with an absolute discretion.

The dictum therefore can be seen as a new kind of buttress of the law that was required in a new kind of society. By virtue of the 10 and the clear analytical framework it suggests of four objectively distinct outcomes, it partakes of the quantitative; by virtue of this apparent transparency and the shove, it partakes of the democratic; and these two aspects together give it one foot in modernity. But the lack of a clear and cogent argument, of rationality, and the lack of a mechanism of policy-making susceptible to democratic oversight leave it with one foot in the pre-modern.

2. The criminal justice system as a problem in binary classification is logically second in the series but was written first. It appeared in the International Journal of Evidence and Proof in October 2018. A pre-print can be downloaded here (an earlier version is on SSRN).

Here I begin to look into the question of measurement:

When we talk of measuring something, we usually think of making observations. However, the observations are meaningless if they are not embedded in a computational framework that allows them to be evaluated. Often this framework is so simple that we don’t even notice it. For example, suppose you are investing $10 and with god-like insight know that policy X would result in the first set of results in the table below and policy Y the second set. Which outcome is better?

$ X 100 Y 1000 Answer: Y. Furthermore, we have a general rule that we can apply to any two options: the bigger number is better.

Now let us turn to the law. Suppose you are trying cases and with god-like insight know that policy X would result in the first set of results in the table below and policy Y the second set. Which is better? More importantly, what is the rule that would allow you to decide between any two sets of results?

True

ConvictionsFalse

AcquittalsTrue

AcquittalsFalse

ConvictionsX 560 1300 7913 385 Y 288 1572 8197 101

We don’t know.

This shows that law has not one but two problems when it comes to measurement: first, the observational difficulty of knowing which cases were rightly decided and which wrongly; and second, the theoretical difficulty of finding a rule to decide on which set of outcomes, X or Y, is better.

I then argue that a sovereign, which is to say anyone concerned about the criminal justice system as a whole and its role in society, cannot ignore either the false convictions or the false acquittals but is obliged to make a decision on the trade-off between them. In formal terms, this means a trade off between two ratios widely used to monitor effectiveness in A.I.:

Precision – the proportion of the convicted that are truly guilty

Recall – the proportion of the truly guilty that are convicted.

Typically courts are preoccupied with precision and the police with recall.

This leads to a solution to the theoretical problem based on the F-measure. We end up with a spectrum of meta-epistemologies in which b2, the number of false convictions we are prepared to trade for one false acquittal, determines a specific meta-epistemology, which is to say a particular framework for deciding on policies. Blackstone’s dictum then can be interpreted as the assertion that “b2 should be set at 1/10″ and can become properly consequential.

3. Measuring justice will appear in the International Journal of Evidence and Proof in 2020 but has already been published through Sage’s “Online First” programme. A pre-print can be downloaded here (an earlier version is on SSRN)

In this I use the theoretical solution and techniques imported from information retrieval to provide a solution to the observational problem. The starting point is the following question: are most of those we convict truly guilty?

One answer … is, ‘I have no idea.’ But who would be willing to endorse that position? It amounts to saying that, when considering outcomes, we have no idea at all whether our system is just or unjust, that we have no epistemic basis for any policy. Though the procedural or ritualistic aspect of justice is understandably emphasised in jurisprudence this should not blind us to the fact that justice is generally considered to be firstly a question of outcomes. Is anyone really prepared to abandon all claims to accuracy?

A more common response I think would be, ‘Yes, I believe so.’ Then, how has that belief been acquired? Is it merely magical thinking with no basis in reality, so that – so far as outcomes go – policymaking in the law is no more than witchcraft in wigs? If not, then it must be ultimately rooted in some genuine knowledge of the outcomes of the criminal justice system, which entails some kind of measurement.

This last seems to me the most realistic account. However, the kind of measurement involved is evidently very different from using a thermometer to measure temperature.

I call this subjective measurement and the point of the article is to show step-by-step how we can move beyond it. The informal and methodologically incoherent are to be replaced by the formal and coherent, the subjective by the objective.

To go this way is to trade one kind of legitimacy for another, the pre-modern for the modern. It is to embrace rather than resist the process Habermas described in which ‘…scientific progress undermines traditional legitimating myths and forces the state to increasingly rely on science as an apparently-neutral basis for political decisions…’ – albeit with the important deviation that the need to make a consequential choice of b2 for the first time means that the effect of this is the exact opposite of the de-politicisation Habermas assumed. Measurement makes the body of the law subject to the sovereign’s panopticon, with the kind of consequences Foucault describes. Control, authority and legitimacy run up and down quantitative wires. Through the technology of trust described by Porter, the current democratic deficit is eliminated. And, as with IQ tests, company accounts and public engineering, this is something done not by the law but to it.

The costs of measurement may or may not turn out to be high, but we can make a comparison with other kinds of measurement systems such as the census, the compilation of economic statistics and clinical trials for pharmaceuticals. The billions spent on these are not regarded as a waste. On the contrary, the measurements they provide are a necessary precursor to good decisionmaking, the clarity they provide essential to improving the trustworthiness and effectiveness of large and expensive systems that are of great importance to us all.

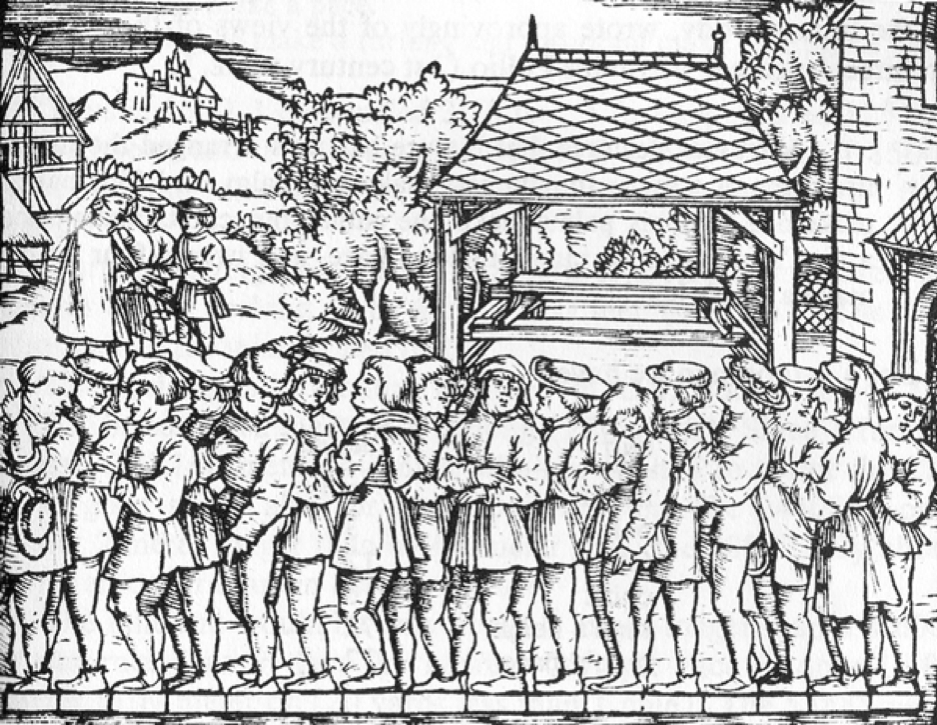

Like a lot of my work it involves pondering apparently obvious basics that we tend to skip over in our rush to apparently more interesting things. One way I slow everything down is to consider what is going on in the illustration above, taken from a kind of textbook of surveying geometry in German from the 1500s.

With both the theoretical and observational problems solved, this gives us the quantitative framework I wanted. The methodological gap is bridged. Through a choice of b2 our democracies can specify (a large aspect of) the kind of criminal justice system we want and provide overarching and consequential guidance to police, prosecutors, judges and legislators. The degree of success of the system can then be empirically measured. This remedies the law’s current quantitative, objective and democratic weaknesses and hence, I think, allows it to properly enter the modern era. I reckon it will also allow the law to become both more trustworthy and more effective.

4. Power Without Control: The Incapacity of Criminal Law

Here I argue that the law’s current, subjective approach to measurement makes it incapable of aiming for any kind of “balance” between false convictions and false acquittals. Equally, when we make a decision about policy we cannot know whether we are making the system better or not. All we can do is to choose to shove the system towards more false acquittals or more false convictions. I argue that these two shoves are the epistemic essence of Packer’s two “models” of crime control and due process.

My technique has an astronomical inspiration. First I establish an epistemic space within which the criminal justice system can move (just as astronomers adopted Euclidean space), then I address the question of movement (just as Kepler established the planets move in oval orbits). There are several different ways in which our capacity to navigate the space can be undermined and the problem for those managing the criminal justice system is analogous to that of sailors before the problem of longitude was solved – they don’t know where they are.

5. Criminal justice as fairness

All this leaves open the question of what justice itself actually consists of. Here I characterise precision and recall as forms of security, public goods in the economics sense and primary social goods in the Rawls sense. By adopting the F-measure as a high-level procedure for determining a conception of criminal justice, a democracy then can make a de jure definition of overall criminal security through a choice of b2. Maximising this F-measure then becomes a social definition of the good. I argue that justice is achieved when we succeed in this maximisation because then everyone in society has a fair chance of having their rights violated as a consequence of low precision or low recall. If we think of these risks like the risk of being shot in a war, then justice lies in making sure that everyone in our society has a fair chance of taking a bullet.

An important conclusion for all the arguments about justice in our society is that, as conceived here, justice cannot and therefore does not exist today.

To read the articles themselves, a bit of legal background is helpful but no mathematics is assumed and you won’t find anything more daunting than a square root. Unless you are really interested in this specialism, the central portion of Killing Kaplanism is likely to prove heavy going – it is an extended passage of close reasoning dedicated to rooting out methodological errors going back 50 years – but the introduction and conclusion flesh out some of the ideas on this page.

About me

If you’ve got questions or would like to be updated about my work, please comment below, use the form or drop me a line at wockbah [at] gmail.com. There are more articles and a book on the way.

I don’t work in a university. If you’re looking for the me that writes about research policy and politics and is now ProQuest’s Research Principal, find me on Twitter, @williamcb.

References

Philip Dawid, Probability and Proof, appendix to “Analysis of Evidence” by T. J. Anderson, D. A. Schum and W. L. Twining, Cambridge University Press (2005). Available at http://www.cambridge.org/9780521673167 (search for “appendix” under the resources tab).

David Hand, Measurement: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press (2016).

H. L. A. Hart, Bentham and the Demystification of the Law, 36 Modern L. Rev., 2–17 (1973) and The Concept of Law, Clarendon Press (1961).

James Franklin, The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability before Pascal, Johns Hopkins University Press (2015).

Larry Laudan, Truth, Error, and Criminal Law, 4, Cambridge University Press (2006).

Herbert L. Packer, Two Models of the Criminal Process, 113 Penn. L. Rev. 1, 5 (1964).

Theodore Porter, Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life, Princeton University Press (1996).

John Rawls, A Theory of Justice Revised edition, Harvard University Press (1999).

Cornelis J. van Rijsbergen, Information Retrieval, Butterworths, online edition at http://www.dcs.gla.ac.uk/Keith/Chapter.7/Ch.7.html, Chapter 7 (1979).

Barbara J. Shapiro, “Beyond Reasonable Doubt” and “Probable Cause”: Historical Perspectives on the Anglo-American Law of Evidence, 241, University of California Press (1991).

Laurence H. Tribe, Trial by Mathematics: Precision and Ritual in The Legal Process, 84 Harv. L. Rev. 1329 (1970-71).

Alexander Volokh, n Guilty Men, 146 Penn. L. Rev. 195 (1997).

Illustration: Jacob Köbel, Geometrei. Von künstlichem Feldmessen, vnd absehen Allerhandt Höhe, Fleche, Ebne, Weitte vund Breite. The original came out posthumously in 1535 but this illustration is taken from an edition of 1598 available in facsimile online at http://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/8074/14/. The book contains three essays on geometry, all of which are useful in surveying; see here for more detail.